Project Description

Our Resources

Trademarked Chemicals in Adwords

The use of trademarks in keyword advertising has in recent years been the subject of a significant body of case law from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and from the national courts of the EU member states. However, the application of this case law to specific categories of trademarked products has so far received limited attention. This article seeks to explore the consequences of the tests set out by the CJEU for the legality of keyword advertising using trademarks registered for chemical ingredients.

What is Keyword Advertising?

Keyword advertising (best known through Google’s AdWords service) is a form of advertising where a search with a given keyword, or keyword combination, triggers the display of an “ad snippet”, which is usually given a prominent location above the so-called “organic” search results (i.e. search results generated by the search engine algorithm). The ad snippet contains basic information, as well as a link to the advertiser’s own website (usually called the “landing page”). The use of keyword advertising has a considerable effect on search traffic, especially for searches performed on smartphones, where the limited size of the display screen gives ads great prominence. The importance of keyword advertising in the modern internet economy is borne out by the fact that in 2017 Google AdWords generated $35 billion in revenue in the United States alone.

One of the key characteristics of Google Adwords and other keyword advertising services is that the advertiser is in principle free to choose any set of keywords to trigger their advertisement; when a user enters the chosen keyword(s) into the search engine, an instant auction is held between the advertisers using that keyword to determine which ads will be displayed. Advertisers are also able to delimit their advertising based on the IP address of the search engine user, as well as through the use of negative keywords. One of the effects of this system is that advertisers are in principle free to choose trademarks belonging to their competitors as keywords. This possibility has given rise to an extensive history of litigation.

Keyword Advertising and Trademark Infringement

While keyword advertising is a global phenomenon, different jurisdictions have adopted markedly divergent approaches as to how the use of trademarks as keywords is regulated. For instance, in the United States the courts have consistently held that the use of another’s trademark in keyword advertising will in most cases not infringe the trademark as long as it is not mentioned in the ad displayed.[1]This is based on the premise that where an ad clearly identifies the party responsible for the ad, the likelihood of consumer confusion is minimised.

The position of European Union law is quite different. Following several judgments[2] on the issue from the Court of Justice of the European Union, a set of clear rules regarding the use of trademarks in keyword advertising has emerged.

The CJEU has addressed the use of trademarks as AdWords keywords by adopting a confusion test: the question to be asked is whether a reasonably observant and circumspect consumer is, on the basis of the advertisement triggered by the keyword, unable to determine if the advertiser is selling goods and services originating with the trademark owner, or is otherwise economically linked to them?[3]Should this question be answered in the affirmative, the use of the trademark as a keyword would negatively affect the trademark’s essential function of denoting origin, and constitute trademark infringement. Importantly, the test contrasts with the US approach in that it does not require the trademark in question to be mentioned in the ad text. The test has been adopted by Google as the basis of their own AdWords trademark policy for the European Economic Area, which provides a valuable out-of-court means for enforcing trademark rights against AdWords.[4]

One question that arises with regards to the CJEU’s test is whether confusion in search engine users can be dispelled through the display of an accurate ingredient list on the landing page. EU law seems to treat the ad triggered by the keyword as use of the trademark in its own right, independent of the website to which the attached link redirects. In Google and Google France, the CJEU suggested that use of a trademark as a keyword may confuse the consumer as to the origin of the goods and services due to the fact that the advertisement in question is displayed in response to the trademark, and is visible on the same screen as the trademark, by virtue of it being the search term.[5] Further, the Interflora judgement specifically referred to the add displayed as the context in which the test had to be applied.[6] It is therefore apparent that the display of an ingredient list, or of a statement denying economic affiliation, on the landing site will not by itself be sufficient to prevent trademark infringement.

In many cases, keyword advertising is used to bring alternatives to established products to the attention of the consuming public. The legitimacy of this practice and its value for stimulating competition has (understandably) been recognised by the CJEU.[7] Often confusion is unlikely as competing products will regularly be advertised under different brand names, enabling them to be clearly distinguished as separate.

Chemical Ingredients

How should the test be interpreted in situations where the trademark in question does not refer to a finished product or service sold directly to consumers, but rather to a constituent part of a retail product, as is often the case with trademarked chemical names? While this issue remains unresolved by the Union judiciary, the case law regarding the Interflora flower delivery network provides the practitioner with valuable guidelines.

In its 2011 Interflora judgement, the CJEU suggested that where the trademark proprietor operates a large and diverse network of independent suppliers, it may be particularly difficult for the consumer to determine whether the advertiser is or isn’t a member of this network in the absence of an explicit announcement.[8] As a result, it is for the national courts to assess, having regard to the relevant circumstances, whether the average internet user is able to determine on the basis of the wording of the ad that the advertiser is not a member of the distribution network denoted by the trademark.[9]

This was relied on by the High Court of Justice of England and Wales[10] and the German Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof)[11] to hold advertisers using the Interflora/Fleurop trademarks liable for trademark infringement. Importantly, the German Supreme Court held that while in most cases the average internet user expects the advertising section of the search results to contain ads unrelated to the trademark proprietor, the size and diversity of the Interflora/Fleurop network meant that the user would expect the advertiser to be a member.[12] At its present state of development, the law seems to be that where an advertiser chooses to utilise a trademark denoting a diverse group of loosely linked economic operators, they are under special obligation to reduce any possible confusion by making best efforts to deny an economic link with the trademark proprietor.[13]

It seems likely that this reasoning would apply by analogy in cases where the trademark at issue concerns a chemical used as an ingredient in retail products. Where a chemical is sold to a large and diverse range of resellers for use in retail products – absent any positive or negative identification from the side of the advertiser – it is nearly impossible for a consumer to determine whether the advertiser is selling the goods of the trademark proprietor. Indeed, they may in many cases expect the trademarked chemical to figure as an ingredient.

This expectation is intensified by the fact that quite often the ads displayed do not mention the trademark itself, even where the relevant chemical is used as an ingredient. Thus, experience with using search engines is unlikely to assist the average user to determine whether the advertiser is selling the trademarked product. The likelihood of confusion is particularly great in cases where a consumer has previously purchased a product containing the trademarked ingredient where the trademark was not mentioned in the keyword ad, and where they as a result have no expectation of the trademarked product being mentioned for it to figure as an ingredient.

One situation that serves to illustrate the possible confusion arising from the use trademarked chemical names and in keyword advertising is that of folic acid. The chemical Levomefolate calcium was developed by the German pharmaceutical company Merck KGaA as a pure, stable crystalline form of naturally occurring folic acid that can be directly taken up and used by the human organism. Merck KGaA markets Levomefolate calcium under the trademark Metafolin, and has been successful in establishing the chemical as one of the most popular folic acid supplements. However, Metafolin is not sold by Merck KGaA directly to consumers, but rather figures as an ingredient in a large variety of branded folic acid preparations sold both by Merck KGaA and other companies.

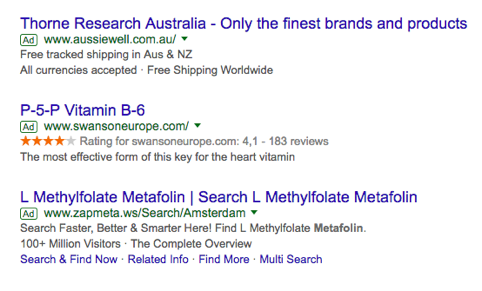

A Google search for Metafolin from a Dutch IP address triggers a variety of AdWords, some of which are shown in the below image.

- Screenshot 12.18.2019

Here, of the three AdWords the third redirects to a search engine, while the second links to the website of an authorised reseller of Metafolin. However, the first ad links to seller not of Metafolin but of an alternative form of folic acid. Faced with a search results page presenting products from a variety of sellers, where the absence of an explicit mention of Metafolin in the ad text does not correlate with the presence of the chemical in the products advertised, it is likely that an average search engine user with no prior knowledge would be at pains to determine that the first ad is in fact not marketing Metafolin, but an alternative product.

Competing Producers as Imitators?

A separate issue is whether keyword advertising is permitted where the trademarked name is used to advertise the same chemical manufactured by an unrelated producer. The CJEU has on several occasions stated that using a competitor’s trademark as a keyword to advertise imitations would constitute trademark infringement where the trademark has reputation.[14] Further, the CJEU has in the context of comparative advertising given the concept of “imitation” a rather wide definition, extending it to cover all situations where a product or its essential characteristics are presented in a way that conveys them having been produced via imitation.[15] Thus, where a chemical created by one company is marketed by them under a well-known trademark, the use of that trademark as a keyword by competing producers could arguably convey the idea that they are imitations of the older, more well-known chemical. However, given that CJEU has placed a clear emphasis on the importance of keyword advertising as a means to stimulate competition in the e-commerce world[16], it is likely that keyword advertising will not be seen as presenting products as imitations unless this is explicitly admitted or clearly implied by the language of the ad itself. This would most likely be the case where the ad contains language of the type “imitation of” or “like” together with the trademark.

While the scope of the imitation argument seems limited to cases where the well-known trademark is explicitly mentioned in the ad, it may nonetheless allow for action to be taken against keyword use in situations where the ad displayed clearly distinguishes between the chemical advertised and the trademark, thereby dispelling any confusion as to the origin of the goods.

Conclusion

From the above it is clear that there is a high risk of infringement where trademarked chemical names are used for keyword advertising. This has a potentially significant impact on the use of keyword advertising for chemical products used in the cosmetic and nutraceutical industries. An important question is whether keyword advertising with these trademarks should be allowed a degree of possible confusion notwithstanding. However, it is arguable that the interest of the advertiser for pointing out alternatives could be served by keywords with the addition in the ad of clear language dispelling the confusion, the presence of which is damaging not only to the trademark owner, but to the consumer as well.

[1] See e.g. 1-800 Contacts, Inc. v. Lens.com, Inc., 722 F.3d 1229, 1243 (10th Cir. 2013)

[2] Case C-236/08 Google and Google France; Case C‑278/08 BergSpechte; Case C‑558/08 Portakabin; Case Case C‑323/09 Interflora

[3] See e.g. Google and Google France, paragraphs 84 and 90.

[4] Accessible at https://support.google.com/adwordspolicy/answer/6118?hl=en.

[5] Google and Google France, at paragraph 85.

[6] See Interflora, paragraph 53.

[7] See Interflora, paragraph 91. With regards to this the Court has held that this does not extend to selling imitations of trademarked products.

[8] See Interflora, paragraph 52.

[9] See Interflora, paragraph 53.

[10] Interflora v Marks and Spencer [2013] EWHC 1291 (Ch) at paragraph 318; while this judgement was overturned upon appeal, the grounds on which the appeal was allowed were different from the High Court’s findings with regards to this point.

[11] BGH, Fleurop, I ZR 53/12

[12] See Fleurop, at paragraph 32.

[13] To this effect, see the Fleurop judgment of the Bundesgerichtshof at paragraphs 39 et sequitur.

[14] Google and Google France, at paragraph 100 et seq.; Interflora, at paragraph 90.

[15] Case C-487/07 L’Oréal and others, at paragraph 75-

[16] Interflora at paragraph 91.